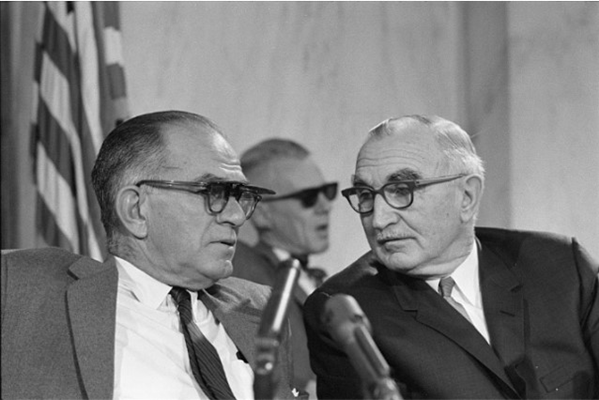

Fulbright Hearings Begin

January 28, 1966

The U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, chaired by Senator James W. Fulbright (D-AR), begins hearings questioning the Johnson administration’s Vietnam policies. Fulbright was once a supporter of the president and helped guide the 1964 Tonkin Gulf Resolution through Congress. But he has come to believe that the regime in Saigon is corrupt and irredeemable and that U.S. escalation of the war is a mistake. Those who testify at the hearings against continued U.S. participation in the war include decorated World War II veteran and retired Lieutenant General James Gavin and diplomat George F. Kennan, the primary founder of Cold War “containment” policy.1

The hearings collectively become known as the Fulbright Hearings and take place intermittently between 1966 and 1971. They are also televised, and the public nature of criticisms raised at the hearings angers Lyndon Johnson. Many historians later argue that the hearings helped turn popular public opinion against the war and gave a larger platform to the antiwar movement.

Senator Fulbright, the chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and a one-time supporter of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, quickly grew concerned with President Lyndon Johnson’s escalation of the war in Vietnam and began holding televised hearings on the administration’s conduct of the war in 1966. These hearings questioned proponents and opponents of Johnson’s war policies, including General Maxwell D. Taylor, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, and diplomat George F. Kennan. Arguing that the deep military involvement in Vietnam detracted from the United States’ larger global interests in the Cold War, Fulbright came to endorse a negotiated end to the war in Vietnam and a withdrawal of all American troops. Although historians question the degree to which these hearings prompted a major shift in public opinion on the war, the televised broadcasts of the debates on Vietnam led many Americans —and women, in particular, since the sessions aired during daytime hours—to begin questioning the conduct of the war.

Historians believe that, as a conservative Southern Democrat, Fulbright helped make opposition to the war more acceptable to the American mainstream. Concurrent with the Fulbright-led sessions, Senator John C. Stennis, D-MS, the chair of the Preparedness Investigation Subcommittee of the Senate Armed Services Committee began holding hearings that criticized Johnson for being too timid in Vietnam. In these meetings, Stennis brought members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) in front of the press to testify that Johnson’s restrictions on bombing and the “limited war” concept prevented the United States from achieving an easy military victory in Vietnam. Historians note that these two opposing congressional viewpoints, simultaneously broadcast to the public via television, deepened divisions in American society caused by the Vietnam War. Fulbright’s hearings made opposition to the war more palpable to the American middle classes, while Stennis’s sessions gave birth to the “stab-in-the-back” thesis, later popularized by Richard Nixon, which claimed President Johnson’s restrictions on the military undermined the ability of the United States to win the war.

Berman, William C. William Fulbright and the Vietnam War: The Dissent of a Political Realist. Kent: Kent State University Press, 1988.

Fry, Joseph A. Debating Vietnam: Fulbright, Stennis, and Their Senate Hearings. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

Woods, Randall Bennett. “Dixie’s Dove: J. William Fulbright, The Vietnam War and the American South,” Journal of Southern History 60, no. 3 (August 1993): 533-52.

Woods, Randall Bennett. Fulbright: A Biography. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.