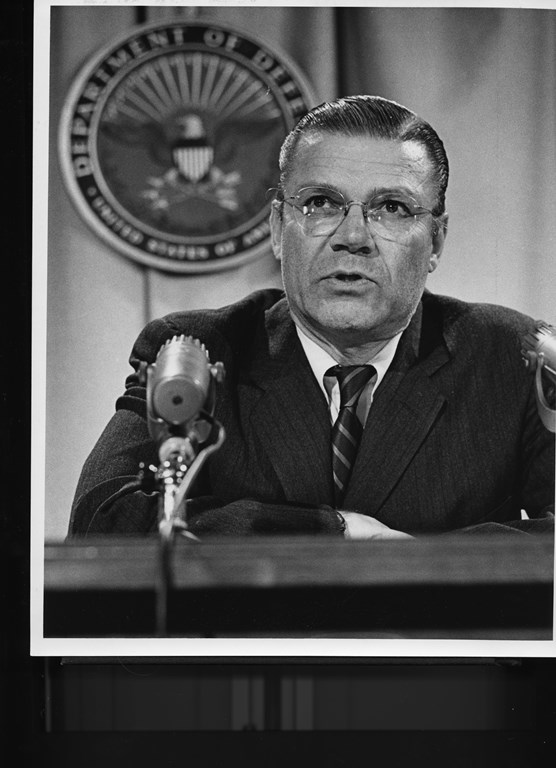

Robert S. McNamara Announces He Will Resign as Secretary of Defense

November 29, 1967

President Lyndon B. Johnson announces that Secretary of Defense McNamara will resign to become president of the World Bank.

As head of the defense establishment since January 1961, Robert McNamara’s aggressive managerial style and his involvement in foreign affairs make him one of the era’s more polarizing figures. By 1966, McNamara publically supports the administration’s conduct of the war, though he doubts the effectiveness of ongoing U.S. military efforts, particularly the bombing campaign in North Vietnam. His opinions increasingly diverge from those of Johnson and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In a May 1967 memo from McNamara to the President, the Secretary asserts that the war is unwinnable and he urges military de-escalation. Their relationship continues to deteriorate until McNamara’s resignation. He remains in office until February 1968.1

What historians say:

Robert S. McNamara had a significant impact on the development of American defense policy in the 1960s, and commenters have often portrayed him as the chief architect of the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War. As Secretary of Defense under President John F. Kennedy, McNamara implemented reforms that enabled the U.S. armed forces to deliver a more “flexible response” to a variety of Cold War conflicts.

In Vietnam, some scholars have argued that McNamara undermined America’s chances to win the war by encouraging President Johnson to fight a limited war of gradual escalation that minimized troop numbers and restricted airstrikes. By employing this strategy, McNamara intended to convince Hanoi that the United States was committed to South Vietnam’s security, but also that Washington was a reasonable partner for negotiations. McNamara’s critics have characterized this strategy as fighting a war “with one’s hand tied behind one’s back.” These historians believe that the United States should have responded to the Communist insurgency in South Vietnam with the full brunt of the American armed forces, involving a declaration of war and possibly an American-led invasion of North Vietnam. These measures, these authors argue, could have halted Hanoi’s aggression against South Vietnam from an early date.

Some historians question McNamara for realizing that a military victory in the Vietnam War was impossible as early as 1966 but nonetheless continuing to fulfill President Johnson’s orders to send more troops and deepen the United States’ commitment to the conflict. To this group of scholars, McNamara’s gradual escalation of the U.S. military presence in Vietnam from 1961 to 1968 provided the leadership in Hanoi with the time needed to improve its defenses and to fine-tune its strategy and tactics. Further, it also reinforced Hanoi’s notion that the United States lacked the resolve to defend South Vietnam for long. McNamara’s strategy also contrasted with the one recommended by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who wanted to use the full force of the United States military against North Vietnam.

Other interpretations place Robert McNamara within the context of a larger cohort of Kennedy-era statesmen, who evidently mismanaged the United States’ Cold-War confrontations, such as the Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba and the war in Vietnam. These critics maintain that McNamara and his peers’ infatuation with quantitative metrics, a management approach cultivated in Ivy League business schools, prevented policy makers from seeing the real problems on the ground in Vietnam. A further critique points to McNamara’s personality as a problem. McNamara’s elite educational background and the “arrogance of power,” this appraisal goes, rendered the Secretary of Defense unable to accept outside advice or criticism from well-qualified subordinates and colleagues, especially members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In McNamara’s memoir, In Retrospect, he insisted that he was too busy during the 1960s to manage effectively the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War, an argument some critics have labeled a hollow apology.

Halberstam, David. The Best and the Brightest. New York: Random House, 1972.

Hess, Gary R. Vietnam: Explaining America’s Lost War. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2009.

Lewy, Guenter. America in Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

McMaster, H. R. Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and he Lies that Led to Vietnam. New York: HarperCollins, 1996.

McNamara, Robert S. and Brian Van De Mar. In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam. New York: Times Books, 1995.

Shapley, Deborah. Promise and Power: The Life and Times of Robert McNamara. Boston: Little Brown,1993.

Summers, Harold G. On Strategy: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War. Novato, CA: Presidio Press,1982.