Week of November 12

On November 12, 1965, U.S. Army forces began searching for the North Vietnamese Army troops who were operating in South Vietnam’s rugged Cao nguyên Trung phần (Central Highlands). Following a Communist attack on a Special Forces camp near Plei Me, intelligence indicated that a sizeable North Vietnamese regular force remained in the area, and that they were being resupplied and reinforced via the Hồ Chí Minh Trail from across the border, in Cambodia.

The next day, after learning that these North Vietnamese forces were somewhere in the Ia Drang River Valley, U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam directed elements of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division—commanded by Colonel Harold “Hal” Moore—to lead an airmobile assault into the area, locate, and destroy any Communist forces that could be found. The battle that developed in the days that followed became one of the most significant and infamous battles of the Vietnam War.

Moore’s units had an official complement of 633 troops, however only about 430 were available for the assault. The rest had been assigned to other duties, were laid up with malaria, or had expiring enlistments. Moore’s orders were to take his troops into the Ia Drang, where they would be supported by air and artillery based nearby. Due to a shortage of replacement parts in the area of operations, Moore’s men were also short on the UH-1 Iroquois “Huey” helicopters that carried them into battle. With only 16 Hueys available, the cavalrymen would need to be shuttled into combat with multiple separate lifts, spaced at least 30 minutes apart (the amount of time it took to unload men at the landing zone, fly back to base for more troops, and return to the field). This meant that the first 80 men on the ground would be on their own in hostile territory for at least half an hour.

Using intelligence from multiple reconnaissance flights to select from a number of possible landing zones, Moore chose a clearing at the base of a cluster of hills and ridges, near the Cambodian border, called the Chu Pong Massif. Its name was Landing Zone X-Ray. The landing zone was large enough for the available helicopters to land together, and it was covered in tall elephant grass, short scrub trees, and giant anthills. These elements provided some cover and concealment, but they also made observation and reconnaissance difficult from ground level and foxholes.

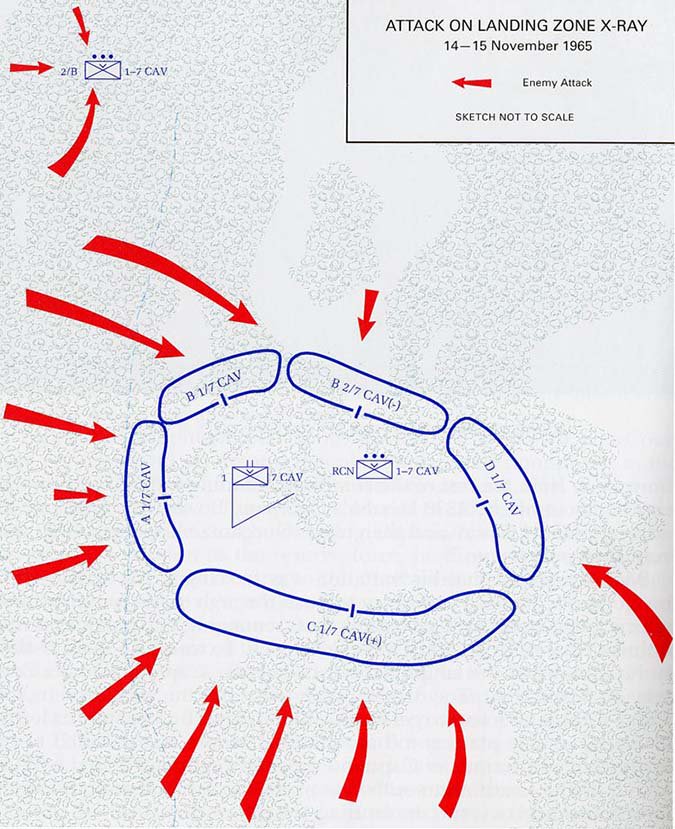

Hal Moore and his command unit boarded their Hueys on the morning of November 14, 1965, to be the first flight into LZ X-Ray. By 12:30 pm, three lifts had managed to arrive, but thereafter the Americans began to face heavy small arms and machine gun fire from the tree line and the slopes of the Chu Pong. As Moore and his troopers would eventually find out, they had landed in the immediate vicinity of a large North Vietnamese force---parts of three battalions and between 1,600 and 2,000 men. The Soldiers of the 1st Cavalry were vastly outnumbered.

A day of intense combat unfolded on November 14. The U.S. cavalrymen took heavy casualties, but with the aid of air and artillery support they inflicted the same and more on the North Vietnamese soldiers. The riflemen, forming a tight perimeter around the landing zone, successfully repulsed every attempt to overrun their position. Huey pilots kept them supplied with ammunition and provisions, despite withering enemy fire whenever they approached. Many aircrews also repeatedly evacuated wounded and dead men, putting themselves at even greater risk in the process, since their helicopters necessarily had to spend more time on the ground and presented large, slow, and irresistible targets.

As darkness fell on the first day of the battle additional reinforcements arrived. The cavalrymen remained completely outnumbered and nearly surrounded, but they had held their position despite the long odds. Wounded and dead comrades surrounded them as they settled in for a long night spent besieged by enemy soldiers, who tested their perimeter defenses frequently throughout the night.

The battle of the Ia Drang Valley raged for several more days. It became one of the most significant and memorable battles of the war. It represented the first time U.S. troops engaged a significant North Vietnamese Army force, and it was the first major airmobile assault in the history of warfare. The 1st Cavalry’s efforts prevented the North Vietnamese from setting up more permanent bases in the Cao nguyên Trung phần (Central Highlands), and U.S. commanders noted that the battle proved the viability and advantages of airmobile warfare.

Please come back next week to read more about the Ia Drang battles of 1965, including the conclusion of the fighting at LZ X-Ray and the harrowing fight at Landing Zone Albany.

For the most detailed account of the battle, see Hal Moore and UPI journalist Joseph Galloway’s first hand account, We Were Soldiers Once . . . and Young: Ia Drang---the Battle that Changed the War in Vietnam (New York: Random House Publishing Group, 1992).1

1Harold G. Moore and Joseph L. Galloway, We Were Soldiers Once . . . and Young: Ia Drang---the Battle that Changed the War in Vietnam (New York: Random House Publishing Group, 1992); John M. Carland, United States Army in Vietnam: Combat Operations: Stemming the Tide, May 1965 to October 1966 (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 2000), 113, 115–17, 120–22, 133, 136–40, 145–50; Stanley Karnow, Vietnam: A History (3rd revised edition; New York: Penguin Books, 1997), 493–94; Spencer C. Tucker, ed., The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History (2nd edition; Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2011), 527–29.

|

Sketched map depicting the attack on Landing Zone X-Ray, November 14–15, 1965. (U.S. Army)